I was walking beside the lake close to our house yesterday when I came on a beautiful planting of yellow daffodils and – of course! William Wordsworth’s famous poem came to mind. when he all at once saw ….

“A host of golden daffodils, Beside the lake, beneath the trees, Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.”

I was delighted, not only to find my own “hosts’ but to find the poem so aptly describing the scene in front of me. And then I read the next few lines……..”10,000 I saw at a glance, tossing their heads in sprightly dance.”

Ten thousand!!!! I couldn’t imagine wild daffodils stretching out before me as they must have in mid – nineteenth century Lakes District, England when Wordsworth wrote the poem. It must have been a magnificent sight.

I was curious if Wordsworth’s daffodils were still blooming in England and the answer is yes! and probably because of Wordsworth. His poem is so well known that daffodil gardens and parks are common in the District and tourists flock there between the end of February and the end of April, when daffodils blooms most profusely.

If you’re a little confused about the difference between daffodils, jonquils, you’re not alone. Technically, they are all in the “Narcissus” genus. Daffodil is a common name for everything in the genus and Jonquils only refer to Narcissus jonquilla – but the name is misused so often it’s become (almost) acceptable for all kinds of narcissus.

Greek mythology tells us how narcissus plants came to be: Echo was a mountain nymph who fell in love with a beautiful young man, Narcissus. He was a vain youth who cared for nothing except his own beauty and spent all his time looking at his reflection in a pool of water. He spurned Echo’s love until she finally faded away, leaving another but her voice. The gods, angry with Narcissus because of his vanity, changed him into a flower who was destined always to sit by a pool, nodding at his own reflection.

Although I love Wordsworth’s poem, it is not my favorite quote about Narcissus. That belongs to Mohammed, who is said to have written:

“Let him who hath two loaves sell one, and buy the flower of narcissus: for bread is but food for the body, whereas Narcissus is food for the soul.”

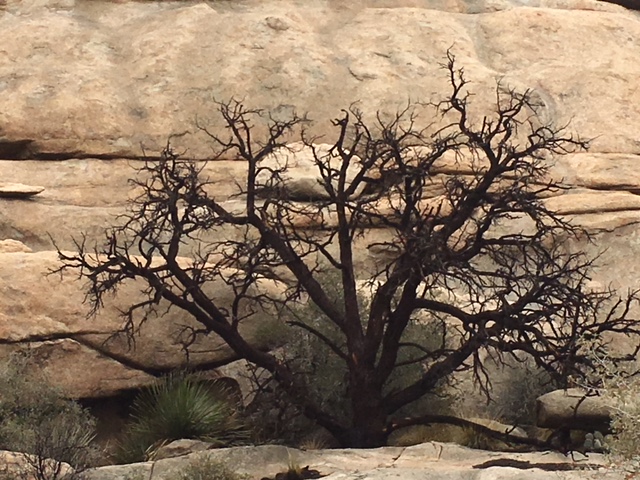

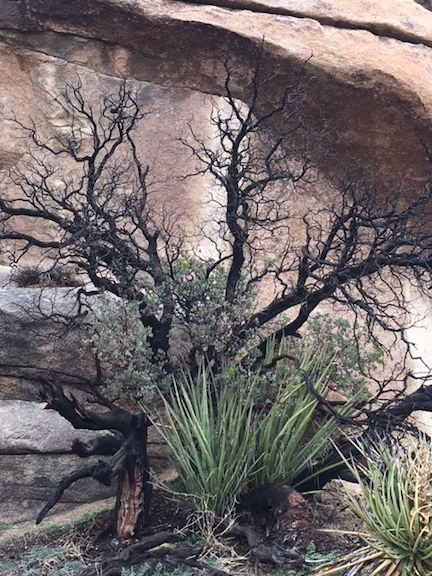

I set out to write about saving the hemlocks. It’s no secret that our beloved eastern hemlocks are being killed by the thousand by a tiny insect called a wooly adelgid. But the deeper I got into the research about the hemlock and the devastating infestation of adelgids, the more I realized that the real story is not about the trees but about the people trying to save them.

I set out to write about saving the hemlocks. It’s no secret that our beloved eastern hemlocks are being killed by the thousand by a tiny insect called a wooly adelgid. But the deeper I got into the research about the hemlock and the devastating infestation of adelgids, the more I realized that the real story is not about the trees but about the people trying to save them.

I love cranberry relish – but only if it is homemade from fresh cranberries. Canned “cranberry sauce” tastes nothing like the real thing (sort of like canned green beans have little resemblance to fresh ones.) And NOW, at the peak of their harvest season, is the time to enjoy these tart little berries.

I love cranberry relish – but only if it is homemade from fresh cranberries. Canned “cranberry sauce” tastes nothing like the real thing (sort of like canned green beans have little resemblance to fresh ones.) And NOW, at the peak of their harvest season, is the time to enjoy these tart little berries.