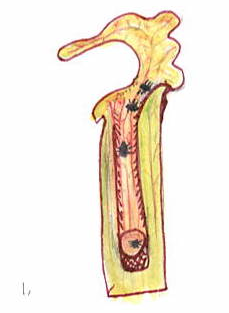

If you think that all carnivorous plants are the “vampires of the plant world,” you would be only partially right. Pitcher plants, the various species of the genus Sarracenia, are more flesh eating than blood sucking. They do indeed trap and eat their prey, but they do it in a way that seems completely benign – unless you happen to be the beetle or fly that actually ends up as lunch. Unlike plants such as the Venus fly trap which move fairly rapidly (at least for a plant!) pitcher plants don’t move but lure insects in with a sweet, delicious scent.

Over the eons, the pitcher plant has evolved many ways to insure that insects who actually land on the plant don’t escape. The lip is sticky and the slippery hairs inside the pitcher are pointed downward making the insect’s downfall almost insured. Once something falls into the rich mixture of liquid death at the base of the pitcher, all hope is gone as a combination of enzymes and acids begin immediately to dissolve the juicy parts of the insect, leaving only the exoskeleton as proof of its demise.

Though this is pretty unfortunate for the insect! it is a marvelous way for the pitcher plant, which makes its home in wetland areas, to supplement its nutrients. But even with this protein rich diet, pitcher plants are in trouble. It’s not vampire hunters but builders and developers who, over the decades, have drained, paved over and eliminated over 90 percent of the wetlands in the southeastern United States.

The result of this massive loss of habitat is that three Sarracenia species are listed on the federal endangered species list and several others appear on lists at the state level. This makes it a genus of great environmental concern. The fine scientists at the Atlanta Botanical Gardens are addressing this situation and have developed a Sarracenia Plant Collection which is accredited by the Plant Collection Network, a program of the American Public Gardens Association.

The goal is to not only preserve and maintain species of Sarracenia but to conserve the genetic variability within each species. Look at it this way. If there was only one human couple left on earth, they could, gradually, repopulate the earth but the inevitable inbreeding would result in a loss of vigor and adaptability for those people (remember the European kings?) If, though, there were 20 couples left, the crossbreeding would result (in a lot more fun) and a much healthier and more vigorous population.

The same is true for plants. If we save the seed of just one Sarracenia (or hemlock or orchid or whatever) we can save the species but for how long? Inbreeding would cause weak and depressed plants and the eventual demise of the species. Scientists call this a population bottleneck. All of this is occurring at a time when climate change is challenging plants to be more adaptable than ever before.

To do what they can to protect the genetic diversity of Sarracenia species, ABG scientists are undertaking the massive job of collecting multiple seeds from 50 different individuals within each species and propagating them from various sites in the wild. How lucky we are that these dedicated men and women are working tirelessly to insure that nature will not just exist in our future but that it will be vigorous, strong and vibrant. I am forever grateful for their contributions. Their work gives me hope.

Excellent!

Wonderfully informative, delightfully written! I’m glad to learn of the impressive work undertaken by the Atlanta Botanical Gardens.

Loved your informative update on these fascinating plants. I have fond memories of looking for pitcher plants with my mother when we lived in Pittsburgh.